A second life for digital debris

E-waste collection pilot to be launched soon

March 7, 2019Coming Soon

May 15, 2019Source : This article was originally published on livemint

- A recent global report on electronic waste suggests the need for a circular economy for electronics

- But is something like this possible in India where the informal sector is still deeply involved in the handling of e-waste?

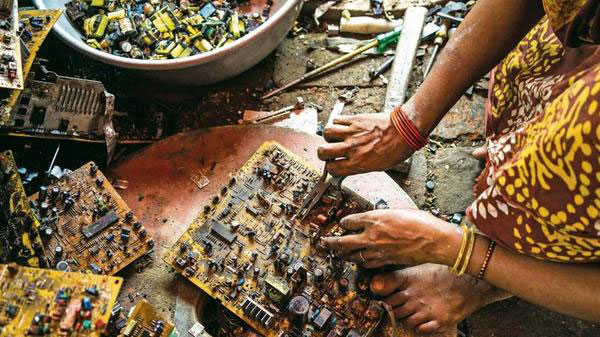

Owais has astonishing hand-eye coordination. The 26-year-old picks up smartphone motherboards, or logic boards, with his right hand, runs his eyes over the integrated circuits (ICs) to see if they are intact, and throws the obsolete ones into a gunny sack. The good ones land in a different container. All this happens in a matter of seconds, the movements smooth and practised, like a reflex.

Another hectic weekday has just begun in the old Seelampur market in east Delhi and Owais is one of the numerous informal workers who are busy sorting electronic waste. It is a sunny March afternoon, but the tall residential and commercial buildings in the area prevent the sunlight from reaching the ground. Owais and I are seated on a raised gravel platform outside a small shop.

He has a lot to do—a big heap of green motherboards sits in front of him, ready for the picking-checking-throwing exercise. “I’ve been doing this for almost 12 years now. So I’m kind of experienced,” he says, showing me his roughened palms and fingertips, when I ask him if he’s worried about injuring himself during the sorting process. He wears no protective gear.

A typical mobile phone is made up of industrial thermoplastics, ceramics, metals and other chemical compounds. Dismantling any electronic item means coming in direct contact with all these elements. Most of the workers in Seelampur do this with their bare hands.

This is how most of the informal e-waste sector in India goes about its business. The e-waste management rules of the Union ministry of environment, forest and climate change (MoEF) mandate that e-waste handlers should maintain a record of the e-waste collected, dismantled and sent to the recycler. But workers in this market seem oblivious to this. Most of the shops are in a shabby state, with little or no space to store the electronic items; much of it lies in the open. On one side of the road, two workers are loading used monitors on to a creaky rickshaw, while others are offloading underground transmission cables from a truck. All these items will either be taken apart here or sent on to scrap dealers.

Reaching the biggest wholesale market for e-waste in Delhi is not easy. The nearest Metro station is Welcome, on the Metro’s red line. A dingy underpass behind the station leads to the north Kanti Nagar area. Traversing narrow lanes, you eventually reach the Shahdara drain, which separates the congested residential area from the market.

The entire e-waste market in the old Seelampur area is concentrated in three-four alleys located parallel to the open drain. As you near the market, known as purani (or old) Seelampur, small garment outlets, butcher shops and sewing machine workshops give way to cramped shops where workers are busy shuffling through central processing unit (CPU) cabinets, server machines, electric motors and smartphones—in cramped working conditions. One fixture outside every shop is a weighing machine; the alleys are like minefields, with broken CPU cooling fans and wire strands strewn all around.

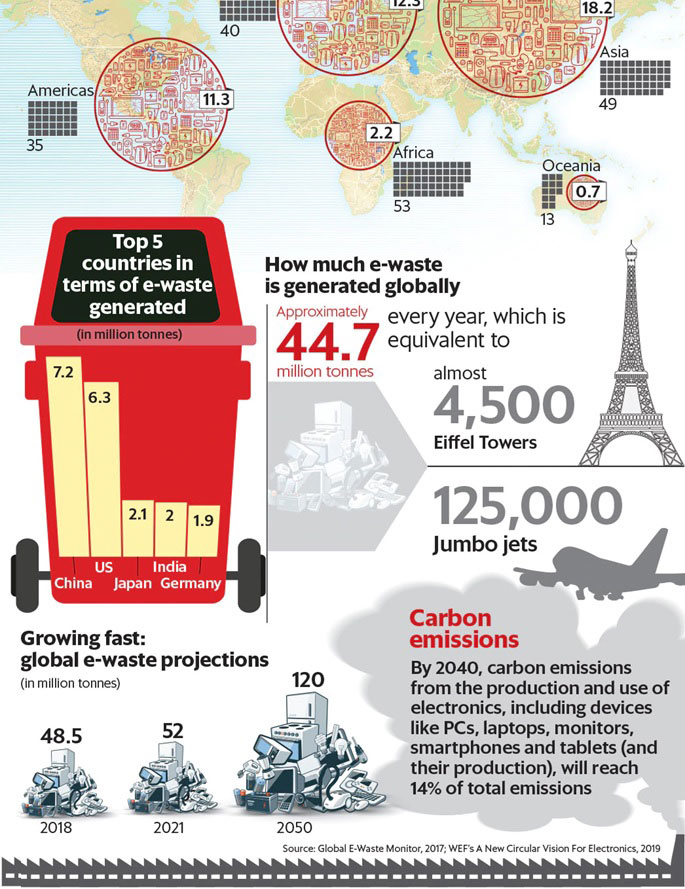

According to a report titled Global E-waste Monitor 2017, a collaborative effort of the United Nations University, the International Telecommunication Union and the International Solid Waste Association, the total e-waste generated in Asia in 2016 was 18.2 million tonnes (mt). India’s share of this was around 2 mt. The report adds that India generates a tremendous amount of e-waste and even imports it from developed countries. The Monitor says over “one million poor people in India are involved in manual recycling operations”. A January Assocham-EY report on urban waste management solutions in India states that according to the Central Pollution Control Board, India has 214 authorized recyclers/dismantlers. In 2016-17, the recyclers treated only 0.036 mt of India’s 2 mt of e–waste, the report adds. Multiple studies and reports have estimated that almost 90% of the electronic waste in India is collected and processed by the informal sector.

Despite global rules seeking to regulate the export and import of e-waste, a new World Economic Forum, or WEF, report (A New Circular Vision For Electronics: Time For A Global Reboot) released in January suggests that large amounts are still shipped illegally. For instance, e-waste generated in Western Europe makes its way to China and India, among other countries. India has become one of the biggest dumping grounds. The report adds that in total, 1.3 mt of undocumented discarded electronic products are exported annually from the European Union. A July 2015 report in the environment publication Down To Earth says that according to estimates of the Directorate General of Foreign Trade, illegal import of e-waste in India stood at about 50,000 tonnes annually.

“The movement of waste in the informal sector in India and its ability to access waste from both institutional and individual generators is significant. When this waste enters the informal sector, it does not come back to the clean channels,”says Satish Sinha, associate director at Toxics Link, a Delhi-based environmental group that has been working on the policy side of waste and chemical management for over two decades. Toxics Link was one of the first organizations to study the electronic waste sector in India. In 2002-03, it released the report Scrapping The High-Tech Myth: Computer Waste In India, studies for which were carried out through extensive fieldwork in Delhi.

Electronic waste is now the fastest-growing waste stream globally.Worldwide, the Global E-waste Monitor 2017 report pegs generation at 44.7 mt. By 2021, projections estimate it at around 52 mt. This number is expected to reach 120 mt by 2050. The UN has termed it a “tsunami of e-waste”.

The WEF report suggests that a circular economy model in the electronics sector could not only increase the longevity of the products but also create better and safe jobs for informal workers. A circular economy, as opposed to today’s linear economy, would be a system where all materials, components are kept at their highest value, i.e. in good shape and working condition, at all times and in use for as long as possible. The report adds that to build a circular economy for electronics, products need to be designed for reuse, durability and safe recycling.

Going by the rules

The E-Waste (Management and Handling) Rules, 2011, were the first such regulations in India. Earlier, electronic waste was covered under the Hazardous Waste Management (HWM) Rules, 1989. The 2011 rules, which came into effect in May 2012, introduced the concept of EPR, or extended producer responsibility, making the producer or manufacturer responsible for the life cycle of the product. In other words, producers would be accountable for the collection of used goods, their recycling and final disposal.

In 2016, producers were given specific e-waste collection targets under EPR. The revised collection targets came into effect in October 2017. The rules were again amended in 2018, and included some changes in collection targets.

Under EPR, companies, producers and OEMs (original equipment manufacturers) are responsible for their products when these are discarded. So, producers pay for the cost of the collection, transportation, recycling and responsible disposal of these products. “The moment cost is externalized to waste, it becomes a challenge. If you internalize the cost, it becomes easier to handle. This is the significant difference and that is why EPR exists,” Sinha says.

Chinese mobile maker Xiaomi has a “Take-back & Recycling Programme” that adheres to the 2016 rules. The programme, started in October 2017, allows users to fill up an e-waste recycling form after logging into their Mi account. An authorized recycler then picks up the e-waste. Users can hand over mobile phones, chargers, power banks, headphones and other electronic products sold in India, irrespective of the brand. For every pick-up request, users also get a discount coupon that can be used for future purchases. “We have partnered with Karo Sambhav to set up over 1,100 e-waste collection points at Mi Homes and Mi authorized service centres in over 500 cities across India… We have collected over 60,000kg of overall e-waste in 2018 alone,” says Muralikrishnan B., chief operating officer, Xiaomi India, on email.

Even Apple, which recorded global iPhone sales of 64.5 million units in the fourth quarter of 2018 (September-December) according to Gartner research data, has a “GiveBack” programme that allows users to ship their old devices to a recycling partner.

Gurugram-based producer responsibility organization Karo Sambhav works with around 28 brands to meet their collection targets and conduct awareness programmes on their behalf. Pranshu Singhal, Karo Sambhav’s founder, says the introduction of EPR has led to quite a few solutions. “The focus has been on how to ensure that the collection is done by the informal sector, since it’s a livelihood issue, in a safe manner, but ensuring that the waste moves to responsible recyclers once it is collected,” says Singhal.

Worldwide, 67 countries have legislation in place to deal with e-waste, according to the WEF report. This normally takes the form of EPR. But while this keeps a check on the e-waste being generated within a country, it doesn’t effectively check the export of e-waste to developing countries like India.

Export to developing countries is regulated under the Basel Convention on the Control of Transboundary Movements of Hazardous Wastes and their Disposal. It has been ratified by 187 countries, including India. Apart from listing hazardous waste, it requires all the countries involved to agree in writing to any transboundary movement of waste. The hazardous waste should be packaged, labelled and transported in conformity with international rules and standards.

When e-waste is gold

The real problem begins when these obsolete electronic items reach informal markets like the one in old Seelampur or places like Uttar Pradesh’s Moradabad, one of the biggest e-waste recycling hubs in the country. For this waste stream can contain up to 60 elements from the periodic table. Every product that comes through is different. Multiple brands have different manufacturing standards and use numerous elements, making the extraction and recycling process tricky.

Yet the economic value of e-waste can be immense, particularly from metals such as gold, silver, copper, platinum and palladium. According to the WEF report, there is 100 times more gold in a tonne of smartphones than in a tonne of gold ore. However, extracting these elements is not easy. “Processing e-waste is really difficult because of the presence of different elements. For instance, when you are trying to extract gold through hydrometallurgy (using a leaching agent), then you have to leave the other things out. Sometimes the cost of recovery is higher than the recovered value,” says Akshay Jain, founder of e-waste management company Namo E-waste.

We are meeting Jain at his recycling unit on the outskirts of Delhi, near the heavily industrialized Faridabad area. To demonstrate how even a small smartphone needs precision dismantling, Jain shows me a makeshift cardboard box that contains components from a disassembled mobile phone. These include small LCD screens, speakers and earpieces, aluminium sheets and the phone’s plastic body. While some of these parts can be used again, most of it will be sold to scrap dealers for a nominal amount on a per kilogram basis. Some of the parts are sold for as little as ₹10 per kilogram.

Jain takes me on a tour of the recycling unit, which is spread across 75,000 sq. ft. However, unexpected rain makes it dangerous to be near the e-waste raw material, so Jain decides to show me the room where the refurbished products certified by the company are stored. Everything, from laptops and tablets to e-book readers, is stacked neatly on metallic shelves. There are similar inventory rooms for other bigger IT products: CPUs and computing servers that can be reused after repair.

“Refurbishing is the best method and least polluting way of recycling. These refurbished products, the IT goods specifically, are available for 30% of the price of a new product. In turn, it’s also making technology accessible to the underprivileged,” says Jain, as we head to the disassembly room where workers are busy dismantling flat-screen televisions on a proper disassembly line. This room is also equipped with gas extraction shafts.

As the rain subsides, we move to the messier region: the sorting area for metals and plastics. It is here that the true nature of electronic waste is laid bare. Workers, wearing surgical masks and gloves, are busy tearing down washing machines and sorting out the plastic that will be thrown into shredding machines. On the other side of this sorting area are hundreds of iron, copper and aluminium bales that have been extracted from scrap and compressed. These bales will eventually be sent to foundries for final recycling.

One has to be careful in these surroundings. “Do you see this foam?” Jain says, pointing to a small pile of insulation foam used in refrigerators that has been shredded to pieces and will be processed or recycled soon. “You can’t touch it with your bare hands. It will keep itching for hours because of the sulphur and phosphorus in it,” he adds.

The setting at this recycling unit is diametrically opposite to the disorganized conditions in places like Seelampur. “We don’t have the infrastructure to handle the amount of e-waste that’s hitting us, either in India or globally. That’s a big problem. We also have a set of manufacturers who are manufacturing for use and dispose,” says Manvel Alur, founder of the Bengaluru-based non-profit EnSYDE India.

Planned obsolescence

The short life of electronics has been a much debated issue, especially in IT products. In industrial design, this policy is known as “planned obsolescence”, a deliberately implemented strategy that ensures any current version of a given product will become out of date or obsolete within a known time period. This means that consumers will eventually need replacements.

This is where EnSYDE India comes in. Since 2003, it has been working with companies, NGOs and institutions across India to reduce their environmental footprint. It designs and implements solutions—based on the behavioural patterns of the stakeholders involved—that improve resource-use efficiency, specifically in the areas of energy, water and waste.

One of EnSYDE India’s recent initiatives is the “bE-Responsible E-Waste” programme, for which it has partnered with Saahas, a non-profit working in the field of waste management, which handles the logistics for the initiative. Started in November 2016, the aim is to encourage people to manage their e-waste responsibly. “We basically go and sensitize the community—schools, RWAs (resident welfare associations) and households—through different campaigns and formats. Once the stakeholders are on board, we start off with the collection system. We have a pick-up truck that goes to different locations. The second option, which is really popular, is the public drop-off boxes. We currently have these e-waste drop boxes in 32 locations across Bengaluru,” says Alur.

The programme has covered around 40 wards in Bengaluru so far, reached out to more than 600,000 citizens and collected 29 tonnes of e-waste. Saahas also has a tie-up with recyclers authorized by the Karnataka State Pollution Control Board to ensure that the e-waste collected is disposed of responsibly.

Treasure from trash

One of the many recommendations in the WEF report suggests the need for advanced ways of recycling and recapturing. A paper published in 2018 by the UK-based Ellen MacArthur Foundation (Circular Consumer Electronics: An Initial Exploration) says certain industry actions, if implemented, could drive the transition towards a circular economy. The use of automation in the disassembly and refurbishment processes could be one such move. “Improved automated processes can increase the number of products that can be treated and reduce the time they require to be treated,” the paper adds.

A recycling procedure on similar lines was launched recently in Australia by Prof. Veena Sahajwalla, who heads the Centre for Sustainable Materials Research and Technology (SM@RT) at the University of New South Wales, Sydney. In April last year, Prof. Sahajwalla launched the world’s first e-waste microfactory, which is capable of transforming components from e-waste items into valuable materials for reuse. It uses small machines and pre-programmed robots to select different components from different e-waste items such as mobile phones, computers and printers.

“The discarded devices are first placed into a module to break them down. The next module involves a special robot to extract useful parts. Another module uses a small furnace to separate the metallic parts into valuable materials, while another one reforms the plastic into a high-grade filament suitable for 3D printing,” she says on email. “These microfactories can operate on a site as small as 50 sq. m… and can be located wherever waste is stockpiled. This can be done at remote and regional locations and is perfectly suited to the systems that are already in place in India,” says Prof. Sahajwalla, who started working on the idea of developing an e-waste microfactory more than 10 years ago.

Alur says bringing out the value of different components in e-waste is “really not rocket science”—she cites the organization’s work in managing medical waste (which involves unused or expired medication) as an example. “Your vitamins, supplements: They all have high-value ingredients that can be put back into the soil and improve its fertility. We are working with organizations downstream which extract these ingredients, put them into compost and resell it,” says Alur on the phone. “Of course, the rest of the waste which cannot be recycled has to be incinerated but the remaining items have huge potential for being valuable again,” she explains.

Refurbished products are another solution. The Ellen MacArthur Foundation paper cites research which shows that up to 50% of users would be willing to have used or refurbished products. Built on insights from over 40 interviews with leading companies and researchers, the paper is based on research supported by Google and was undertaken by the foundation in 2017.

User perception, of course, varies. Some users, such as “techies” or “fashion-oriented” users, may not be interested in refurbished products, but these groups only represent part of the market, the paper adds.

“The trust in a refurbished product is important. I need the assurance that I’ll get equally good service from a refurbished product as I would from a new one. What is the kind of warranty that I am being provided? Can I flaunt it? These are some of the things that need to be addressed,” says Sinha.

Organizations are starting to recognize e-waste’s hidden economic value and reusability. Take, for instance, the 2020 Olympic Games in Tokyo—all the medals will be made from precious metals collected from recycled e-waste. More than five million used phones were collected from among 47,488 tonnes of discarded electronic devices, after a nationwide scheme was launched across Japan by the Tokyo 2020 Organising Committee in April 2017.

In Delhi, the Prakriti Metro Park near the Shastri Park Metro station is another example of how junk, including e-waste, can be recycled and put to good use. The park features 12 sculptures made from 20-25 tonnes of waste by artists from across India.

Back at the old Seelampur market, not far from the Prakriti Metro park, Owais and three other workers have managed to sift through the heap of smartphone motherboards by the end of our conversation. “The ones that are intact will be used again. These ones (he points towards the gunny sack) will be sold to the scrap dealers,” says Owais.

One of the workers places the sack on a weighing machine. They have gathered around 3.5kg of electronic waste. Owais is done for now. He cleans his hands and pulls his Android smartphone out of a pocket to check some WhatsApp messages as he waits for the next lot of e-waste to arrive.